The Panacea Society was originally called ‘The Community of the Holy Ghost’, and was made up mostly of women. Its leader was Mabel Barltrop – the widow of an English clergyman, and mother of four children– whose followers called her ‘Octavia’.

During the 1920s, followers of the Panacea Society moved to Bedford to live near Octavia. Eventually, the community was able to combine the gardens of several properties to form ‘the campus’ – a private space between the community houses, with a chapel at its centre.

From this headquarters, the Society operated a religious organisation which reached across the world. Over two thousand people became members of the Panacea Society, in Europe, North America and many parts of the British Empire and Commonwealth.

From its beginning, the Panacea Society expected the end of the world. Society members were convinced that God would soon act to bring about a new age – a period of peace and happiness called ‘the Millennium’.

The Panacea Society was part of a wider religious movement of groups concerned with prophecy. The Panaceans believed that God was speaking to them through Octavia, but her followers did not believe she was the only modern prophet. Rather, they accepted a lineage of seven prophetic voices since the late 1700s – a tradition they called ‘the Visitation’.

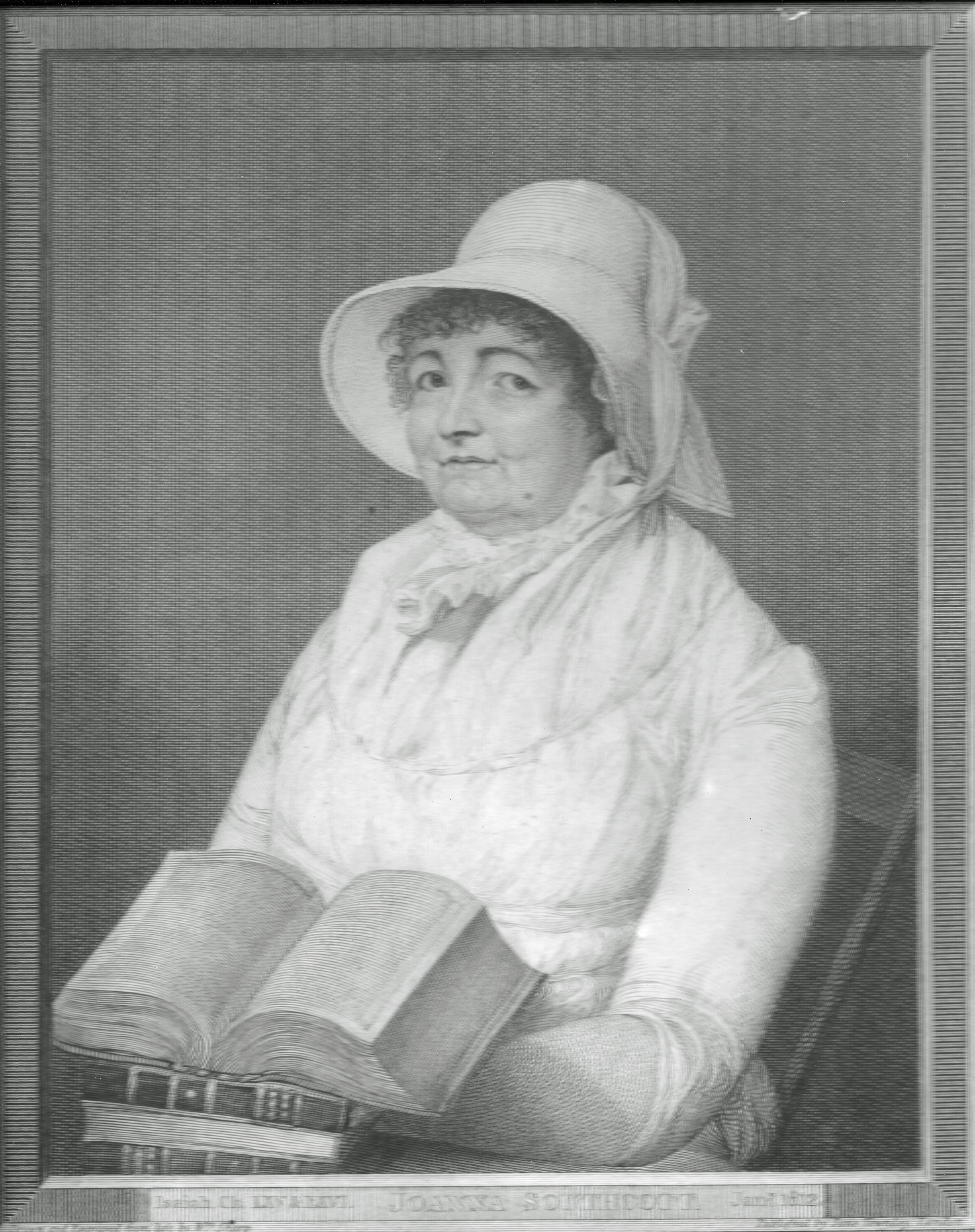

Joanna Southcott born in 1749 was the second prophet of the visitation. Her published books of prophecies and attracted thousands of followers in her lifetime. She claimed that God had told her to prepare people for the Millennium; but that God needed to send another messiah before Jesus returned. This figure was called ‘Shiloh’.

In 1814, Southcott’s many followers were convinced that she would give birth to a baby Shiloh. When Southcott showed the signs of pregnancy – despite being 64-years-old and a virgin – extraordinary preparations were made for the messiah.

After 10 months Southcott died and no Shiloh was found. But some believers in the Visitation spent the following century awaiting not only the Millennium and the Shiloh, but also a further event: the opening of a sealed box of prophecies Southcott had left behind.

In 1804, Joanna Southcott had sealed a selection of her prophecies in a box and declared that it should only be opened in a time of national danger, by 24 bishops of the Church of England. Over the decades, this box was kept safe by her believers, ready for when the bishops requested it.

When the First World War began in 1914, many believers in Southcott’s prophecies thought that this must be the predicted time of national danger. A number of different groups and people tried to persuade the bishops of the Church of England to open the box.

The campaign to persuade the Church of England to open the box brought the early members of the Panacea Society together. They came to believe that Octavia was also the Shiloh Messiah, the embodiment of the spiritual daughter of Joanna Southcott, and the daughter of God.

During the 1920s and 1930s, the unopened box remained central to the Society’s beliefs and activities – and for decades they continued to expect the bishops. In Bedford, the community made detailed preparations for the day the box would be opened.

It is an intriguing paradox that, during these most active years when members made every attempt to persuade the church to open Joanna Southcott’s box, they did not actually have it in their possession.

Since Southcott’s death it had been kept hidden in successive Southcottian homes. In 1861, the box passed to the Jowett family of Yorkshire. At this time, the first photograph of the box was taken and a description printed. The surviving ‘Old Southcottians’ –also carefully compiled letters and documents to support the authenticity of their box.

The box remained in the hands of members of the Jowett family until 1957. No Jowetts ever joined the Panacea Society, but they supported the Society’s attempts to persuade the bishops to open the box. When the last Jowett believer died in 1957, he left the box along with associated material to the Panacea Society.

The Panacea Societies commitment to keeping the location for the Box a secret was absolute. Eventually, the Society confirmed that they had the box but did not allow it to be photographed until 2002. Its location remains a closely guarded secret to this present day.

The Panacea Society worked hard to make everyone in Britain aware of Joanna Southcott’s Box and the need to convince the bishops to open it. Their campaign reached across the country, through leaflets, public-speaking and, most importantly, advertising, including billboards in central London. The Society spent large amounts of money on its campaign because it was considered vitally important to the future of the world.

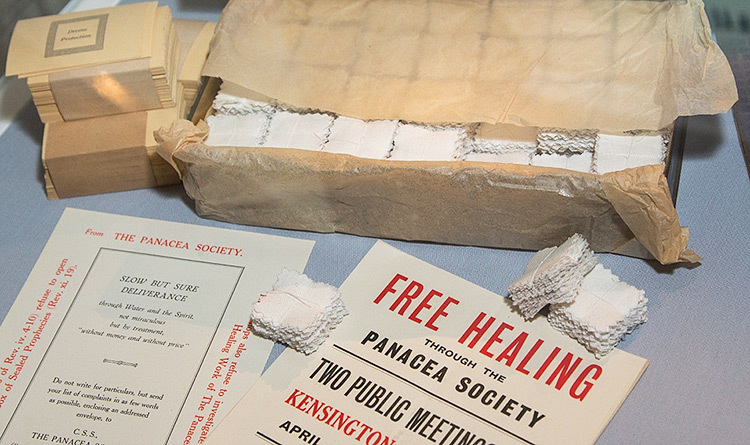

The Panacea Society became well known for the campaign to open the box but few people remember another national advertising campaign promoting their Panacea. The community believed it had discovered a healing cure for all illness.

The cure was ordinary tap water over which Octavia had breathed and prayed. The water could be drunk or applied externally to the body depending on the ailment. Every ‘water-taker’ received precise instructions about the water and how to report back to Bedford on their progress.

The ‘blessed water’ was also believed to have protective properties. Panaceans sprinkled the water to protect homes and public buildings, and were given cards to carry, marked ‘Divine Protection’.

Originally the healing water could only be distributed to members of the Society living close to the headquarters but demand from non-resident members prompted the development of a new method of transferring the healing power believed to be in Octavia’s breath. In a ceremony Octavia first prayed then breathed over long rolls of linen, which were then cut up into one-inch squares. Anyone applying for healing would be sent one of these small squares of healing linen. They were instructed to keep the linen square in a jug of water, and pray each time they used it.

Interest in the Panacea Healing spread all over the globe, over 120,000 people have applied to the Panacea Society for healing since it began.

Members of the Society meticulously archived the extensive correspondence from recipients of the healing squares replying whenever possible and the resulting archives are a fascinating record of faith and health from around the world. The Society continued to distribute its healing cure until the last member died in 2012.

Octavia died on 16 October 1934. Her death was shocking for all those who believed Octavia would live forever in the Millennium. At the moment of Octavia’s death, her followers waited for her resurrection. But after four days a coffin was ordered and a funeral arranged. No single person could replace Octavia’s leadership; she was, after all, still considered the messiah. But others kept up the community’s traditions and the community continued, and even grew in the late-1930s.

Although many of the early members of the Panacea Society lived through the Second World War to the 1950s, the number of resident members declined rapidly during the next 50 years. Despite this the Bedford community continued, governed by a Council of appointed members and run by committees and annual meetings. By 1965 there were just 21 resident members and during the 1990s the number fell to less than 10.

Faced with a large number of empty and dilapidated houses and an ageing membership it was clear the Society was unlikely to continue in the long term but the few members left were faced with challenges posed by the legal status of the Society.

In 1926 Octavia had set about putting the Panacea Society ‘on a new, strictly business-like basis’. She felt the group’s already considerable funds should be in the hands of trustees. Legacies could then be left to the Society rather than to her as the representative of it. As a result, The Panacea Society was registered as a charity with a set of clear aims.

During the 20th century the Society continued to accrue funds through tithes paid by members, rental from its properties, and the income from investments.

Although the governing council allocated some income to advertising and promotion of its causes, by 1996 the Society had built up a substantial reserve fund. So much so that it prompted the Charity Commission to insist that they could not continue to save for the fulfilment of their aims at an unspecified date in the future. If the Panacea Society was to maintain its charitable status, it needed to modernise its charitable aims, management and administration and dispose of its surplus assets.

There followed a period of turmoil for the few remaining elderly members who believed passionately that the return of Christ was imminent and that the money they had saved would then be vital. But faced with the reality of their members’ advanced age and a declining membership, the council decided to close the Society to new believers and make reforms that would allow it to continue to operate as a charity working towards the furtherance of the Christian religion.

In 2001 the council appointed its first professional trustees. They approved a large auction of the Society’s surplus assets and increased the rental prices of its properties to reflect commercial rates. A new grant-making program was launched to provide funds for research into historical theology and for the relief of poverty and sickness in the Bedford area.

With the help of professional advice the last members of the Society continued to take an active role in its administration. In 2012, following the death of the last member, the organisation changed its name to The Panacea Charitable Trust, marking the end of the Panacea Society as a religious community and announced the completion of a new museum that would tell the story of the Panacea Society.