Written by Museum volunteer Alison Smythe

International Women’s Day last month (8th March) was a great opportunity to think about the women of the Panacea Society. As a new volunteer at the Panacea Museum I was immediately interested in learning more about how a group of women in 1919 came to form a religious community in Bedford. In 1930 the Panacea Society had around 50 members residing in Bedford, in and around Albany Road. Men did occasionally become members of the society but the majority of followers were women. This piece tries to understand why the Panacea Society had predominately female members.

The Panacea Society attracted some of its female followers because it was underpinned by Southcottianism. Joanna Southcott, a self-described religious prophetess who gained a large following in the late 18th century until her death in 1814, espoused an alter-narrative of Christianity where women were given a central role. Southcott claimed that ‘if woman was responsible for the ‘fall’ of mankind only woman could achieve ultimate redemption’. In the Bible, it is Eve’s actions in the Garden of Eden that lead to the fall of mankind. Southcott, and subsequently the Panacea Society, believed it was only a female redeemer in the original Garden of Eden that could overcome sin and end suffering on earth. Mabel Barltrop, the founder of the Panacea Society, was believed to be the female redeemer, eighth prophet of the Visitation and Daughter of God, ‘Octavia’.

Mabel Barltrop

Mabel Barltrop

Joanna Southcott’s writings re-emerged in the early 20th century at a time of social change and tension surrounding women’s role and their rights. Her writing was to some women incredibly profound and relevant to their situation and experiences. During the First World War, 6 million men were mobilised. As women assumed some of the roles of men in the workplace and in the family, they had become active citizens but were still excluded from holding positions in the Government and in the Church. In a society where women were disenfranchised and marginalised, Southcott’s narrative and box of prophecies created a community where female followers had a voice and were they felt their actions could bring about change.

As historian Jane Shaw explains ‘this new interest in Southcottianism dovetailed with the women’s suffrage movements, which were regarded by Southcottians as fertile ground for potential converts.’ It was believed Southcott’s box would guide the nation through its time of danger – the Great War and it was Southcott’s female followers who felt empowered to see an end to the world’s suffering. Like the suffragette movement, the Southcottians from the early 20th century onwards sought to bring about change in a country undergoing immense upheaval as a result of industrialisation and later the war.

Joanna Southcott

Joanna Southcott

Disillusionment with the Church of England was also a factor in the rise of Southcottianism and later the establishment of the Panacea Society. Mabel Barltrop had been a devoted Christian from a young age, however ‘she felt that the church had given her no satisfactory answer as to why all the people she was closest to, except her aunt fanny and her own children, suffered’ and died relatively young. During WWI there were approximately 700,000 fatalities. British society, particularly women, dealt with an overwhelming sense of loss and grief that the established Church and Victorian culture could not provide an explanation for. The Southcottians believed the Box of Prophecies could guide the nation through this time and had tried to engage the Church. Yet, the Bishops in England refused to open Joanna Southcott’s Box and this furthered a sense of disillusionment with the established Church amongst the followers.

The war had a profound and deep effect on society, culture, politics and religion. The search for answers or religious explanations led to a heightened interest in a host of practises that fell outside of established or non-conformist churches. With families mourning for the loss of loved ones the chance to communicate with the afterlife led to a dramatic rise in the popularity of spiritualism. Against this backdrop of the war in which people began to explore other religious persuasions it is therefore understandable why some women, many bereaved, widowed, unmarried and who felt marginalised by the Church of England, sought to gain answers in Southcott’s and Barltrop’s writing.

The Panacea Society also offered women a sense of belonging to a community, a family and even provided a home. Middle-class women joined the society who had the means to sustain and contribute to the upkeep of the society’s campus in Bedford, but those who did not have the means could work for the society in return for board and membership.

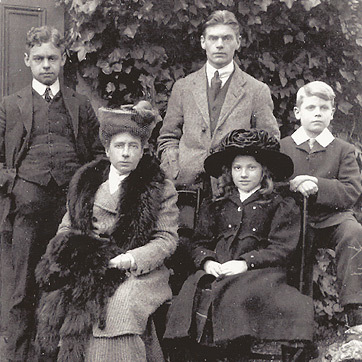

Mabel and the Barltrop Family, before the founding of the Society

Although the society was certainly non-conformist in that it was led and followed largely by women, it was not progressive in the ways we might expect. The Panacea Society prescribed to traditional rules and values that were being challenged in the outside world by the Suffragettes, the industrial revolution and a more secular world view. Some of the female followers of the society would have wanted to ascribe to traditional values including abstaining from sexual intercourse, in order to prepare for redemption and acceptance into the Millennium. Within the Society campus the Panaceans could live a life according to their beliefs and come together in resistance to a radically changing world, in which they saw sin and suffering.

Overall it was Southcott’s alter-narrative of Christianity that attracted female followers, who then came to form the Panacea Society as a branch of Southcottianism. The social change brought about by WWI was conducive to the revival of Southcottianism, but also other nonconformist religious groups. Southcottians were able to effectively target women at a time when they were gaining rights and more independence. Southcott’s prophecies and subsequently Mabel Barltrop’s, struck a chord with women at this time, offering them a voice, alternative answers and a cause to rally behind. The Panacea Society continued in the same vein, but was furthered by establishing the Bedford campus where members could live, learn and worship according to their beliefs.

References:

Jane Shaw, Octavia, Daughter of God: The Story of a Female Messiah and Her Followers, 2011.