Samplers are a rite of passage for many budding needlewomen, serving as both a visual testament to their skill, as well as a chance to express themselves: whether through the inclusion of a particular motto or via their choice of motif. In 1807, Joanna Southcott created a sampler, one of several extant examples of her needlework housed at the Panacea Museum. Framed and kept in a drawer to protect it from further light damage, this now faded and fragile sampler was prized by the Society’s founder Octavia, who studied it carefully and even incorporated it into ceremonies. The Panaceans’ reverence for such a commonplace, domestic item might initially seem misplaced. Yet, this article will show that the Society related to Joanna’s sampler because of its essential familiarity as a medium, using it in ways that revealed key aspects of the Society’s doctrine, underlying their belief in the importance of woman’s work and its ability to connect the domestic and the spiritual.

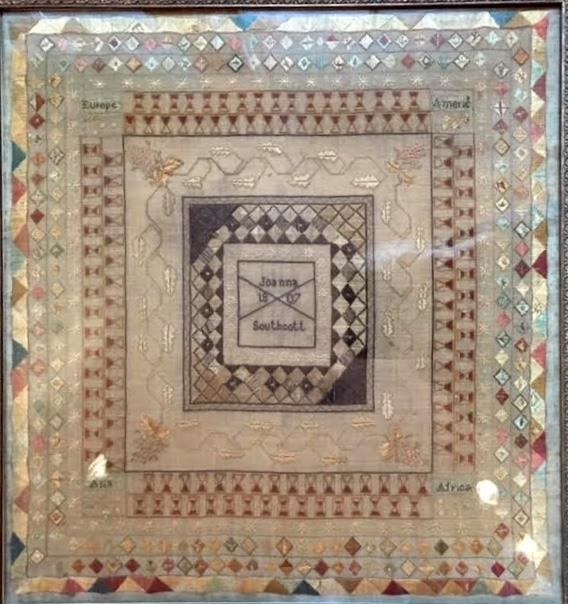

Joanna worked the sampler in silk on wool, featuring a largely geometric design [Figure 1]. At the centre is a square in which Southcott has stitched her name and the date, surrounded by a chequerboard effect. This is bordered by a vine with leaves and bunches of grapes, which is framed by four rows of hourglasses. While the inner row of hourglasses appear uniform, the outer row displays varying levels of sand. Instead of using typically feminine motifs, Southcott has opted for a hard, linear design, which, in its reliance on square shapes, is more reminiscent of a patchwork quilt than a sampler. The unusual pattern, coupled with the lack of an obvious narrative, could be seen to encourage a deeper reading of the work.

Sampler, silk on wool, 1807. Panacea Museum, BEDPM0004

Sampler, silk on wool, 1807. Panacea Museum, BEDPM0004

The sampler came into the Society’s possession on 25 September 1920, when it was given to Octavia as a gift by a ‘K- E-’ [possibly Panacean Kate Ellen Firth]. Octavia saw two clear messages depicted in the sampler: the first, that the hourglasses indicated the amount of time they would have to wait until Christ’s return - at one point, this date was calculated as 1923. The second message related to the central section of the sampler, which, ‘if viewed from an acute angle, takes the form of the Altar of Incense in the Tabernacle’. This is the tabernacle described in the book of Exodus [25-31; 35-40], which served as a temporary, portable temple, akin to a curtained tent, containing the Ark of the Covenant. The altar of incense which formed part of this holy space was intended to be used for offerings. This tabernacle is, therefore, simultaneously a home and a place of submission and sacrifice, much like the Bedford community, where Society members were encouraged to overcome their failings. Indeed, Octavia’s pronouncement on the sampler emphasised this connection with the Biblical tabernacle, describing it as ‘an altar of willing sacrifice’ which necessitated each person ‘to slay the beast, the personal evil within’. The fact that this message of self-discipline was conveyed through embroidery serves to confirm the Panaceans’ interpretation. For many women, sampler making formed part of their feminine education, and was not so much a way of expressing oneself as proof of one’s submission to pious improvement.

Some Museum visitors, upon seeing Southcott’s sampler, may be inclined to think that the Panaceans were reading too much into it. However, the key to understanding why the Society might have studied this sampler so closely lies in Joanna’s process of receiving divine communications. Joanna’s handwriting was so poor that many of her early prophecies could not be deciphered. By 1807, when Joanna stitched this work, her companions Jane Townley and Ann Underwood would write down all that she dictated. With her hands free to work, Joanna could sew whilst in direct communication with God, which lent her needlework added significance. As Rachel Fox noted, ‘These productions might very well have been called “The Prophetic Needlework,” because they accompanied the Prophetic Word.’ The Panaceans therefore believed they could read Joanna’s sampler as though it were one of her writings.

The Society’s attribution of symbolic meaning to Southcott’s work is confirmed by the prophetess herself: much of her needlework was the subject of divine intervention. In 1807, Joanna was making a patchwork covering when she realised she did not have enough pieces to finish it. Her inner voice told her that just as she had needed to incorporate different sorts of fabric to complete the covering, so God would join together ‘all sects and parties’ in the millennium. She was told, ‘the Shadow of what I shall do upon the Earth, they may discern from the works of thy hands,’ investing her typical, everyday, woman’s work with a higher meaning. This covering also shared several motifs with the sampler, namely the hourglass and the repeated use of squares, which showed how God would ‘bring in the Four Corners […] and my hours are Known to me, how fast the sands will run’. Joanna’s divinely ordained needlework represented the tangible joining together of the domestic and spiritual realms. This metaphor was taken up by Octavia, who mused: ‘How can any man say that religion to-day is not a patchwork, bits of truth here and there sewn in with error?’

Although, in this way, the aesthetics of the sampler were secondary to the message hidden within it, the Panaceans clearly found it a striking work. Octavia was impressed by its ‘symmetrical production of beauty’, considering that, owing to Joanna’s being taken over by the spirit while sewing, she ‘was not […] able to make the calculations which women who do such work are in the habit of making’. Conversely, the Panaceans expressed a slight distaste regarding the style of Joanna’s writings, which were often in simple verse. Octavia excused Southcott’s lack of literary style on the grounds that ‘God could not tell Joanna more than a woman of her time and education could bear.’ The Society’s understanding of the changing remit of women can therefore be read through their appraisal of Joanna’s sampler: while, as a modern audience of well-read women, they found Joanna’s literary skills wanting, the sewing skills of ‘a woman of her time and education’ were to be envied. Moreover, they mourned the possible disappearance of this traditional craft due to mechanisation and modernisation.

However, the sampler was not merely a relic of a past time, to be studied and marvelled at; it was given an active role in Panacean ceremonies. On 16 October 1920, Octavia recounted how she had hung her chain of beads over Joanna’s sampler ‘with the thought that her great work may be near accomplishment’. This suggests that Octavia attributed some form of agency to it, in that physically connecting it to such a personal item as her necklace was part of a dialogue with the picture. There is no doubt that the Panaceans felt that this sampler was related to them personally: they considered the design to be composed of eight squares, including the centre, and eight was naturally of immense significance to them, owing to Octavia being the eighth prophet. In this way, Southcott’s needlework was not merely capable of prophesying future global events, but also spoke to the Panaceans about their own particular place in the millennium.

The sampler’s mysterious agency is alluded to again in Octavia’s script from August 1924, which recounts how it fell off the wall and broke a bowl and vase. In becoming capable of movement and destruction, the sampler deviated from its traditional function, which is to decorate a room but remain an otherwise unobtrusive presence. It is interesting to note that 1923 had seen the death of Lord Carnarvon, which popular culture had attributed to a ‘Mummy’s Curse’. While the Panaceans did not see the Southcott relics as being in any way cursed, the idea of spirits being present in objects and those objects exercising power may have been in the popular imagination in a way even the Panaceans would not have been immune to. Furthermore, Octavia’s draping her necklace over the sampler is reminiscent of worshippers offering up material goods to relics or statues. Indeed, protected behind its frame, could the sampler not be seen as a Southcott relic in its glass reliquary?

Joanna’s sampler, therefore, not only represented her prophecies, but also, by extension, her presence. This is suggested by its use in a ceremony on 4 September 1924, in which Emily Goodwin carried out a sort of exorcism in her role within the Society as the Divine Mother. Southcott’s sampler was placed against a brick altar on which was burned members’ confessions [Figure 2]. The inclusion of the sampler is not fully explained, although it would seem to suggest that this makeshift altar was intended to echo the tabernacle of Exodus. Yet, in this same ceremony, a carpet made by the late Ellen Oliver was also included, by being laid in front of the altar. The design of the carpet is not alluded to, as though its importance is defined only by its connection to Oliver. If a member’s needlework could be used to recall her physical or spiritual presence, it can be assumed that this connection applied to Southcott’s work too. Indeed, the very nature of sewing, which often involves long hours sat with the work close to you, makes a piece of needlework a highly personal item.

Southcott’s sampler used in a ceremony in Bedford, undated. Panacea Museum

Southcott’s sampler used in a ceremony in Bedford, undated. Panacea Museum

For the Panaceans, needlework was a personal activity, but it was also an experience shared by many women. When Octavia felt compelled one day to place a sampler made by Ellen Oliver beneath Joanna’s sampler, she was connecting the two women through the sewing which they both had in common. In addition, Octavia outlined a complicated numerological theory which she had inferred from the date of its production. In doing this, the rite of passage which was the childhood sampler was elevated to a devotional relic and a work capable of imparting a useful message, not the decorative, superficial item which women may have believed they were making at the time. After Ellen’s death, Octavia called her the eighth angel, and the importance of her place within the Society’s theology is evident from the reverence shown to her needlework. Sewing was the common thread which enabled women of different generations to connect their experience to that of another. Joanna’s sampler was not just a piece of needlework to Octavia, it was, after all, ‘[her] Mother’s sampler’.

Octavia, who had sewed since childhood, would have learned this feminine activity from her female relatives. This enabled Octavia to understand sewing to be part of the shared experience of women. This is demonstrated by the way in which she related to the biblical figure of Eve: ‘[she] and I are exactly alike […] The difference between her and me is only the difference of the things with which she was surrounded; where she probably made her “apron” with a thorn, my baby’s robe was made with a needle.’ Octavia could best relate to the women of the bible by situating them within her own domestic sphere, as well as by elevating herself to their divine position.

Incorporating needlework into rituals and displaying it on Octavia’s wall could be interpreted as creating deliberately ‘female’ spaces. This practice has primarily been observed in women’s groups of the early twentieth century as a means of staking a claim in a male-dominated landscape. Yet, that intention cannot be applied as readily to a female dominated community performing clandestine ceremonies. Within the context of the Panacea Society, it could be argued that the incorporation of textiles into doctrine and practice occurred more naturally, and instead bears witness to the way in which God was brought into the domestic, feminine sphere. Yet, considering the church’s relegation of women to positions outside of the sacred space of the church, both the bringing of ceremony into the house and garden, and the celebration of something as intrinsically domestic as a sampler, suggest a conscious subversion of liturgical practice.

The traditional feminine sampler has often been maligned by feminist historians, who see it as visual proof of the submissive role foisted on young girls. Southcott’s sampler simultaneously supports and refutes this reading: whereas, on the one hand, Joanna’s undertaking of the work would appear to be a form of obedience to God, its divine attribution also underlines the unorthodox female role which she believed she would play in the millennium. Moreover, the sampler is unusual in style, displaying a creativity which is poles apart from the ‘by-numbers’ examples which are more suggestive of the joylessness of the exercise. The sampler took on yet more meaning when used by the Panaceans. They may have appreciated the sampler as a testament to traditional feminine craft. Yet, its very presence and use in a community which allowed women to carry out rituals and held that only a woman could save the world, upends the notion of humility attributed to needlework. Furthermore, the intrinsic, bodily connection between a woman and her work enabled the Panaceans to use a woman’s needlework to recall her presence once she had died and enabled them to connect their own gendered experience with that of other women.