Servants to the Servants of the Lord- written by Christine Pugh, volunteer at the Panacea Museum.

A display of photographs in the Panacea Museum shows some of the members of the Society in the 1960’s. Amongst them is an image of Gladys Powell in the black and white uniform of a domestic servant, a type of dress then rarely seen even in the grandest house, and which had long disappeared from the villas of the Castle Road area of Bedford. From the beginning, until the end of the Panacea Society- domestic servants kept the community’s houses running smoothly and Gladys was the last of this band of helpers.

When Octavia established the society even modest homes would have at least one resident servant. The ‘maid of all work’ was the least desirable role in domestic service. Its long hours started with lighting fires, and finished with making evening drinks; with scrubbing cooking and cleaning in between. This general role covered tasks that in larger households would have been completed by several different servants. It was usual for a maid of all work to change from the cotton print dress and calico apron of the morning’s heavy work into a traditional black dress and white apron for the afternoons ‘parlour maid’ role. The workload combined with loneliness of solitary tasks, limited free time and low pay made it an unattractive career choice.

Recruitment after the First World War was especially difficult as other work opportunities opened up in factories and shops. A shop girl at the time may have had to work a 14-hour day, but at least at the end of it her time was her own. In 1919 and again in 1923 there were government enquiries into the ‘domestic servant problem’ which offered no successful solution. However, recruitment was less of a problem for the Panacea Society as it offered the only way a woman of little or no ‘means’ could become a resident member.

Those joining as ‘full’ resident members of the Panacea Society were expected to have no debts and sufficient means to support themselves either as a householder or a lodger in one of the community houses. Joining as a domestic servant meant the same access to chapel meetings, working for people who shared common beliefs, as well as a small wage.

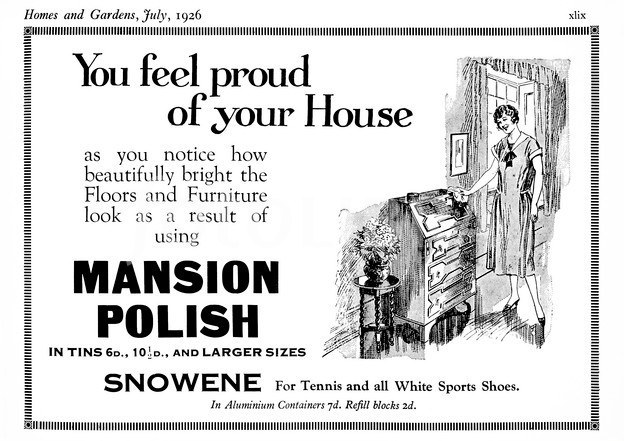

One of the many products used to keep the Society's houses spick and span

One of the many products used to keep the Society's houses spick and spanOctavia in her many writings made it clear that servants should know their place and be respectful. She instructed heads of houses to be ‘be kind, yet know your place as mistress…..There is a standard you must keep. It is this familiarity between mistress and maid that makes a servant expect equality’. In the same document she stated that ‘Servants are indispensable and are a very necessary asset to the kingdom and must not be looked down upon. The labourer is worthy of his hire and food.’

Advice for servants included ‘I want you to be respectful, to tame the tongue, not to criticize, not to be too familiar or inquisitive. Lucifer has trained minds in quite another direction making servants want to be the mistress. Not as the maid, which has caused all this error, socialism etc.’

Octavia’s attention to the detail of daily life in the home may have helped the domestic help as it established clear guidelines on how things should be accomplished and the responsibilities of all residents, so there could be no dispute on how a task should be completed. Octavia was also there to listen to any complaints (later Emily Goodwin was in charge of domestic servants) – although in matters between maid and householder she seems to have judged on the side of householder.

The Panaceans lived modestly. Octavia insisted the servants had the same food as other residents. Servants were able to participate in the chapel services allocated to them but only attended social events in the capacity of domestic help.

The Panacea Society did offer a chance to mix with other servants during their limited time off. There are records of bicycle rides, walks and visits to the cinema. Evidence of friendships are shown in wills, such as Harriet Moss; a Panacea servant who left £100 to Gladys Powell .

The ability of the Panacea Society to recruit domestic help and retain it meant that there was not the investment in labour saving household equipment seen in most houses from the 1930’s onward. Jane Shaw in her book Octavia, Daughter of God describes the houses of the Panacea Society having kitchens with an Edwardian feel even into the twenty first century, for example ranges rather than modern stoves and few appliances. In the latter days of the Society they did employ non-Panacean daily help but with their natural frugality, resisted any major modernization of properties.

Now with the end of the Panacea Society this world has vanished, but glimpses can be seen at the Museum, in the kitchens and scullery of Castleside and in the maid’s simple bedroom in the Founders House.