Volunteer Thomas Vaughan on how the remarkable women of The Panacea Society created a suspended reality to support their unique theology, in 12 Albany Road, Bedford.

This post responds to ideas presented Blog #2: Stopping Time by Leila Johnston (Link attached below). Leila is the current ‘Artist in Residence’ at the Panacea Society and uses the archives of the Panacea Museum to find innovative ways of presenting contemporary views on technology to the CenSAMM (Centre for the Critical Study of Apocalyptic and Millenarian Movements) conference on Artificial Intelligence and Apocalypse.

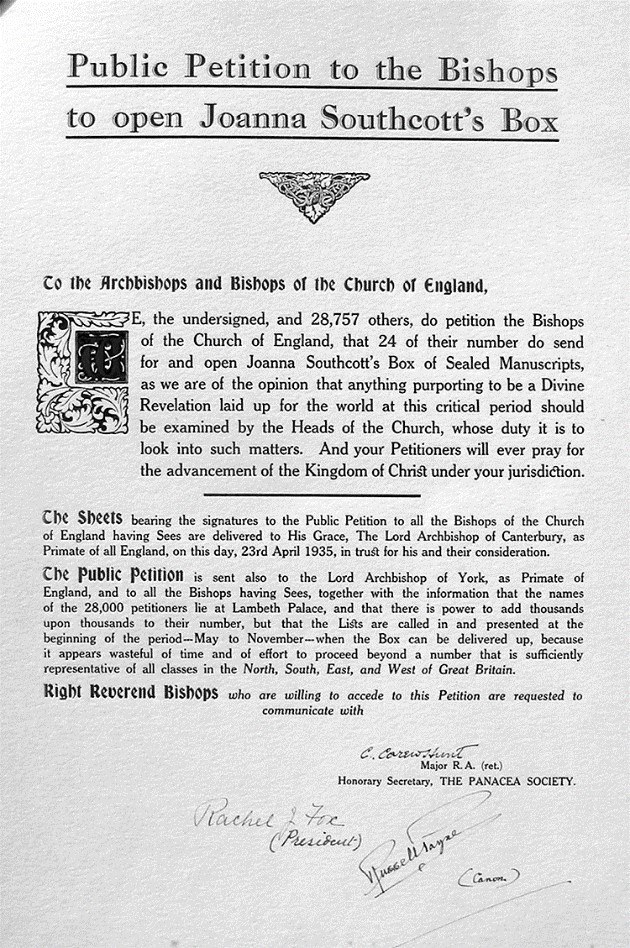

In her blog, Johnston notes that the Panaceans cultivated within the closed walls of their property in 12 Albany Road a single moment of suspended time. Removed from the events an increasingly secular world, the society sought to 'stop time' and to live in divine anticipation. This anticipation alludes to the core purposes and beliefs of the society; to lobby 24 Bishops from the Church of England to open Joanna Southcott's Box of Prophecies, to wait for the revelation of these and Octavia's personal prophecies, to await the second-coming of Jesus Christ and the birth of Shiloh (a messianic and prophetic figure). This notion of living in constant divine suspension is particularly striking when one situates the Panacea Society in a broader socio-political context.

In this article, I want to build on Johnston's thoughts by examining other mechanisms that Octavia (pictured above right) employed to create the impression of an eternal present, as well as demonstrating that her attempt to do so aimed not only to prepare her female followers for the revelation of her prophecies, but also to preserve middle-class domestic values against what the Panaceans regarded as a 'threat from Bolshevism'. These will include the role ritualistic and spiritual processes such as the 'Overcoming' played in sublimating individual and personal histories and lived experience to a common 'Panacean' experience of time and space.

The establishment of the Panacea Society in 1919 can be seen as espousing a conservative middle-class response to great social upheavals taking place in broader society. Secular society was making historically transformative leaps forward; women's suffrage and the creation of a working class consciousness undermined traditional bourgeois British values, whilst also posing great opportunities for vast and new groups. Indeed, this crucial interwar moment situated the fates of all the nations of Europe in closer proximity than they had ever been in its history; the fates of Russia and Germany in the theatre of war suddenly also became that of Britain and its allies. For its part, crippling post-Great War debts and the dissemination of truths about the horrors of the First World War meant that Britain began begrudgingly to accept that it could no longer be the sole architect of its future. Radical and quickening developments on this newly international stage, as well as social developments closer to home, helped to produce within the founding members of the Panacea Society a shared conservatism and sentimentality for the recent past, and a feeling that the values held by its predominantly middle-class female constituency were under grave threat.

For Octavia and her growing like-minded following, these early Panaceans sought to create a religious space which 'stopped time'. Octavia constructed her society based on traditional Middle-Class values, and offered a conservative religious dimension to secular matters. Octavia had to create historical narratives and narratives of futurity which excluded or overlooked the prevailing progressive attitudes in secular society. In order to support its prophetic beliefs and ensure members believed in the society's unique conception of the future there had to be a visual landscape inside the property at 12 Albany Road which made constant reference to their divine mission. It had to, somehow, manipulate their immediate environment so that the occupants understood that their patience in waiting for Shiloh and Shiloh's revelations, for Joanna Southcott’s Box of Prophecies to be opened, and the Second-Coming of Jesus Christ, was virtuous and good. It is with the use of visual mediums and rituals that the society managed to simultaneously 'stop time' and create a new Panacean future.

The property at Albany Road abounds with spaces which aim to create an eternal present, and to remind occupants of their divine mission. One such space contains Shiloh's Cradle. Shiloh is a messianic figure written about only briefly in the Book of Genesis 49:10 of the Hebrew Bible; "the sceptre will not depart from Judah...until Shiloh comes". The Panacea Society, and Octavia in particular, interpreted the figure of Shiloh as a prophet with divine healing qualities. We know from a lengthy letter correspondence between founding members Ellen Oliver and Mabel Barltrop (later known as Octavia) that Mabel understood herself to be the incarnation of Shiloh. This belief accounts for her name change to Octavia, which represents the mystical 8th biblical prophet, Shiloh. The crib, so lovingly maintained and adorned with hand-made clothes for the baby Shiloh, came to symbolise to the Panaceans their existence within Octavia's prophetic narrative for the future. The cradle represents the birth and maturity of Octavia's religious and spiritual wisdom, and that the Panacean women lived within a house and time where the important figures of their religious narratives of futurity, existed and guided them through their daily struggles towards religious redemption. The cradle continued to provide a focal point for Panacean faith even after the death of the supposedly immortal Octavia in 1934. The cradle was maintained as a way of demonstrating commitment to the Panacean faith and belief in the Panacean historical narrative of redemption and reincarnation. Perhaps the continuation of the Panacea Society (the last member dying only recently in 2012) long after the death of its prophet can be partially understood due to the strong symbolism in spaces like Shiloh's Cradle. Indeed, the belief held by members after the death of Octavia that she would likely soon return, along with Jesus Christ, was made more plausible by the presence of such spiritually pertinent and symbolic visual material.

Various rituals which took place within the Panacea Society also played a crucial role in 'stopping time' for newly admitted Panaceans. The ritual which came to be known as the ‘Overcoming' sought to prepare these women for eternal life and immortality on Earth in the event of Jesus' Second-Coming. In the words of historian Jane Shaw, the Overcoming "actively tried to rid oneself of one's personality, of one's very self." (P99) Octavia placed such importance upon this activity that in a paper she wrote for use in the community she notes "Were it required of me to emblazon a Legend over the gates and doors of these buildings... it might run thus: 'Leave Self behind, all who enter here!' “This radical process had a spiritual function; to abandon the contents and belief in self-hood was to rid oneself of selfish desires, and to relinquish the soul of sin and evil. We gain an insight into one of the key means through which Octavia hoped to rid her followers of what she saw as sinful individuality through another paper she wrote and distributed for use within the society; The Manners Paper. This paper sought to school the community on what Octavia saw as proper Edwardian etiquette. The most striking aspect of the paper is how extensively it underscored the importance of simple domestic conduct between residents of the community; the paper warned that those whose teeth clicked when eating toast must abandon its consumption altogether, precisely how to lay the table for each season, how to enter one's own room so as to reduce noise irritation for residents residing in rooms below, how to properly eat asparagus (with your fingers, apparently), which days to go shopping for bread, are just a few of the details noted in the paper. As the community expanded throughout the 1920s, reaching its peak capacity of around 50 women, papers of this sort became circulated all the more frequently. It may seem to us excessive or even pedantic of Octavia to have paid such obsessive attention to banal acts, but strict adherence to a single set of rules set forth by Octavia played a crucial role in assimilating women into the Panacea's vision of the future. The energy dedicated to writing, following, and encouraging 'good convivial conduct' in the most minute of domestic habits, reinforced the overall objective put forward in 'The Overcoming'; if one had to constantly regulate one’s own behaviour in mundane situations such as the way guests are received or ensuring the proper name for a table napkin (not a serviette, apparently) was used, then little room is left for individuality, and a fixed ideal of the 'correct' Panacean woman emerges. Installing a constant concern for the wellbeing and happiness of others in the society helped the women assimilate completely into the community, and to see themselves not as 'individuals' with a unique past and future, but as single religious parts of a continuingly evolving whole, with a shared heritage and divinely ordained future.

These ideals, so deeply entrenched in documents like the Manners Paper and practises like the Overcoming, also reflect conservative sentiments within the Panacea Society. Whilst correcting manners within the domestic sphere of 12 Albany Road may seem a harmless non-political activity, one should view the valorisation of traditional middle-class values within their proper socio-political context. A constantly recurring message in Panacean propaganda of the 1920s claims that the 'Bolshevik threat' can only be quelled through the opening of Joanna Southcott's Box of Prophecies. This core message was spread by means of leaflets (printed on the Panacea's own printing press), public speeches, and the renting of billboard spaces in key London sites such as tube stations and Piccadilly Circus; one such billboard reads: “MOSCOW’S FATE WILL BE LONDON’S DOOM- UNLESS THE BISHOP’S AGREE TO OPEN JOANNA SOUTHCOTT’S BOX.” Although the parallel between a burgeoning Socialist Russia and the importance of etiquette for 50 middle-class women in Bedford cannot be directly drawn, the intensity of focus on manners and etiquette does indicate a concern on behalf of Octavia; that traditional British manners were indeed under threat and in need of preservation. This perhaps goes some way to explain the detailed codification of manners in the Manners Paper, and helps to illustrate another method through which the Panaceans resisted developments outside of their society, to preserve and protect their own sense of morality from the erosion of time.

The creation of the ideal ‘Panacean Woman' through rituals like the Overcoming and the Manners Paper meant that a great deal of what made new members of the society 'unique' in secular society had to be shed, in order for them to inhabit their new identity as 'Panacean Women'. Perhaps one of the most extreme cases of this female transformation was of Ellen Oliver, a founding member of the society in 1919. A suffragette before joining the Panacea Society, her transformation must have been a particularly radical one, with suffrage for women achieving the first stage of its success only recently in 1918, with women aged 25 and over eligible to vote, and equality with men being reached in 1928. Oliver's resignation from the suffrage movement just at the moment it seemed to be making substantial progress represented a violent upheaval of selfhood. Ellen Oliver's story was by no means unique, and presumably many of the women who joined the society throughout the 1920s experienced similar upheavals of their personal identities in order to assimilate into the society. Such an upheaval, however, proved essential to the successful running of the society; relinquishing deeply held ideas about the self narrowed the horizons of one's future, aligning them to the accepted vision of the society as one of a community awaiting the bounty of spiritual rewards (such as immortality) that were sure to come when the prophecies of Octavia came good. By leaving their own pasts and identities behind, these women accepted the Panacean vision of the future. With rituals like the Overcoming aiming to dilute selfhood and increase uniformity amongst its adherents, this future could feel like the shared ambition in which all Panaceans were entitled. As much as these women were inhabitants within the Panacea Society, the vision of the future fronted by the Panacea Society surely inhabited them.

To us, as a British public and largely secular 21st century beings, it may seem irrelevant to discuss how this society understood and experienced time. After all, much of the ideological appeal that lay behind the creation of a millenarian society like the Panacea has been lost to the obscurity of time. Upon closer inspection, we are not trying simply to uncover lost theologies of minor religious movements like that of the Panacea, nor are we simply trying to comprehend how wonderfully unique they were. In fact, this article and the ongoing research at the Panacea Museum hopes to better understand how these women rationalised their beliefs. We must not forget that while the society saw its popularity peak in the giddy confusion of ideas and narratives in interwar Britain, it continued to function on a global scale until 2012. As I hope this article has led you to agree, religious fervour does not suffice to explain this great feat. It was through a unique understanding of futurity made malleable and present, disseminated through ritualistic and visual mediums to a receptive following of middle-class women, that the society of the Panacea was able to suspend time, like a fly in amber.

Link to Leila Johnston’s Blog Post: http://censamm.org/artist-in-residence/blog/leilas-blog-2-stopping-time

Book Referenced throughout: Jane Shaw, Octavia, Daughter of God: The Story of a Female Messiah and her Followers, Jonathan Cape Random House 2011

Photo Credit: Panacea Society Archives